Is democracy dying? Here's why — and what to do about it.

In the 35 years since the fall of the Berlin Wall, democracy has been in retreat around the world. Can we build new designs that help it flourish?

This year we are commemorating the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II — an important milestone not only because it marked the end of the bloodiest global conflict in history, but because it ushered in the institutions that catalyzed a long and unprecedented period of relative peace, prosperity, and human advancement.

But now those structures are showing signs of wear, and we're challenged to develop new designs to carry democratic values into the 22nd century.

On May 8th, 2025 (the 80th anniversary of V-E day) I delivered a talk at TEDxBerlin offering a critical look at why democracy has foundered in the 35 years since the fall of the Berlin Wall. Here's a summary of that talk, which you can watch here.

Democracy Doesn't Spread by Itself

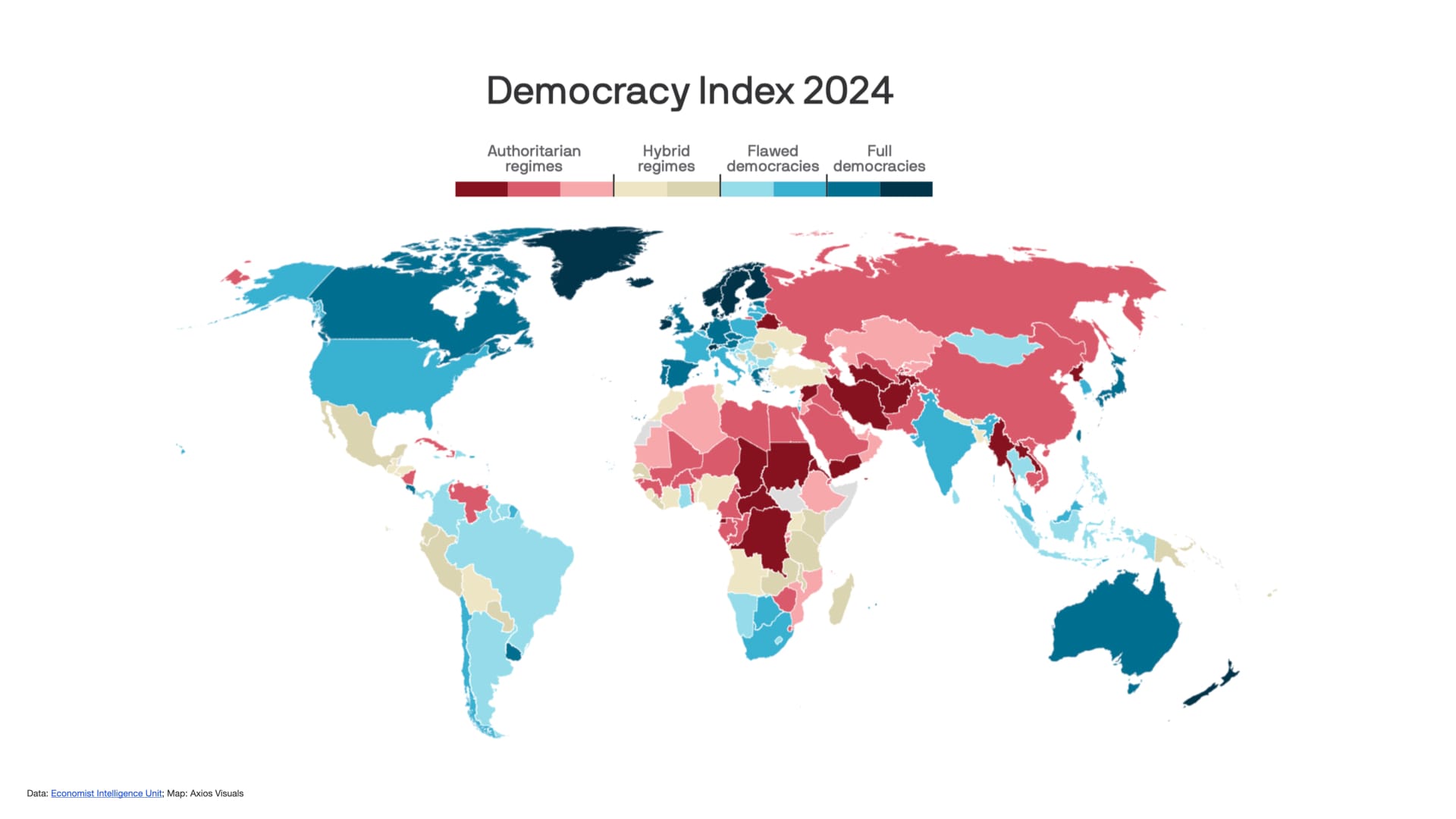

When the Berlin Wall came down in November 1989, there was a sense that democracy would flourish as the Soviet system collapsed. In the 35 years since, we have had a chance to run a natural experiment, and the results are in: democracy is not spreading.

Globally, there are fewer democracies, and many of the world's largest democracies are now considered “flawed” and showing signs of strain. And according to the Economist Intelligence Unit, 39% of the world's population is now under authoritarian rule.

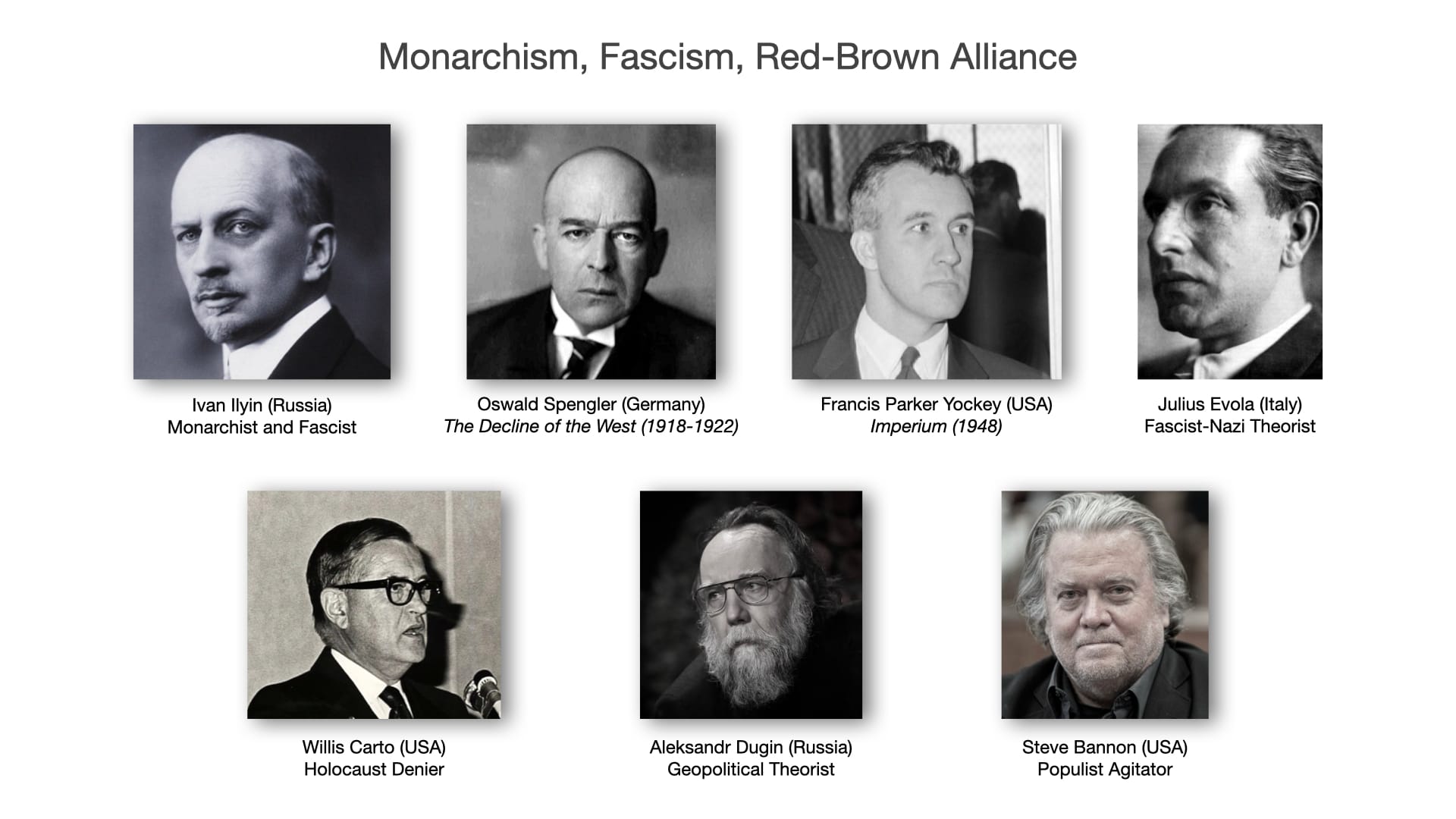

There is also a long line of people who have advocated against democracy and actively worked to hinder it. Fascist theorists and monarchists have collaborated for over a century to develop ideologies that could counter democratic impulses and provide an “alternative” worldviews, usually rooted in eugenics, social Darwinism, and hierarchy.

That impulse has run straight through from Ivan Ilyin in Russia, to Oswald Spengler in Germany, Julius Evola in Italy, to Francis Parker Yockey and Willis Carto in the United States. Aleksandr Dugin has absorbed all these ideologies and more and networked with Steve Bannon to export them throughout the West.

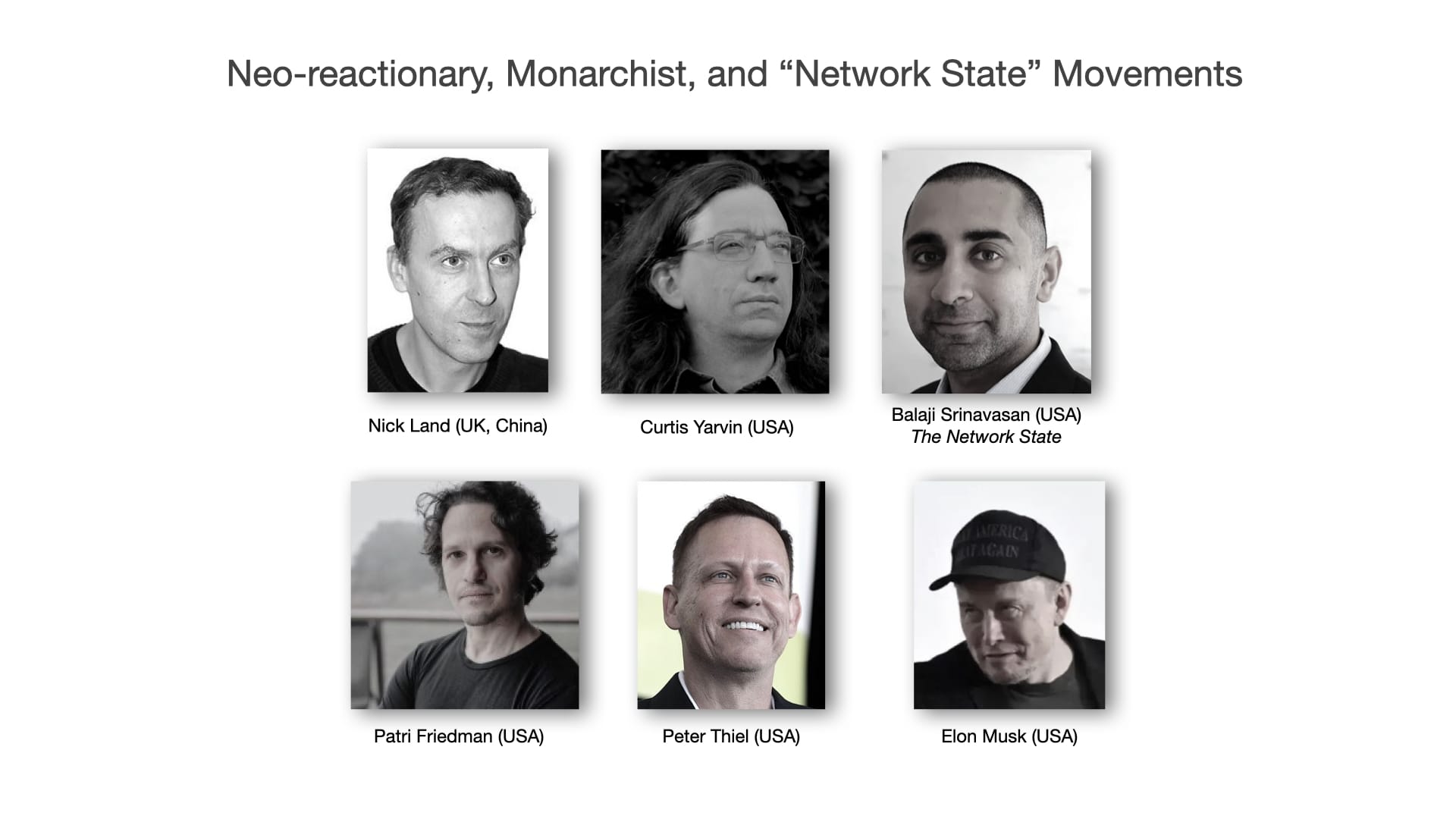

And lately, another strain of neo-reactionary tech libertarians, from Curtis Yarvin to Peter Thiel and Elon Musk, has become increasingly powerful, pouring their influence and wealth into shaping election outcomes and effecting regulatory capture. It's no wonder that democracy isn't spreading when powerful backers are growing increasingly more aligned with illiberal ideologies.

Russian Cosmism and Esotericism

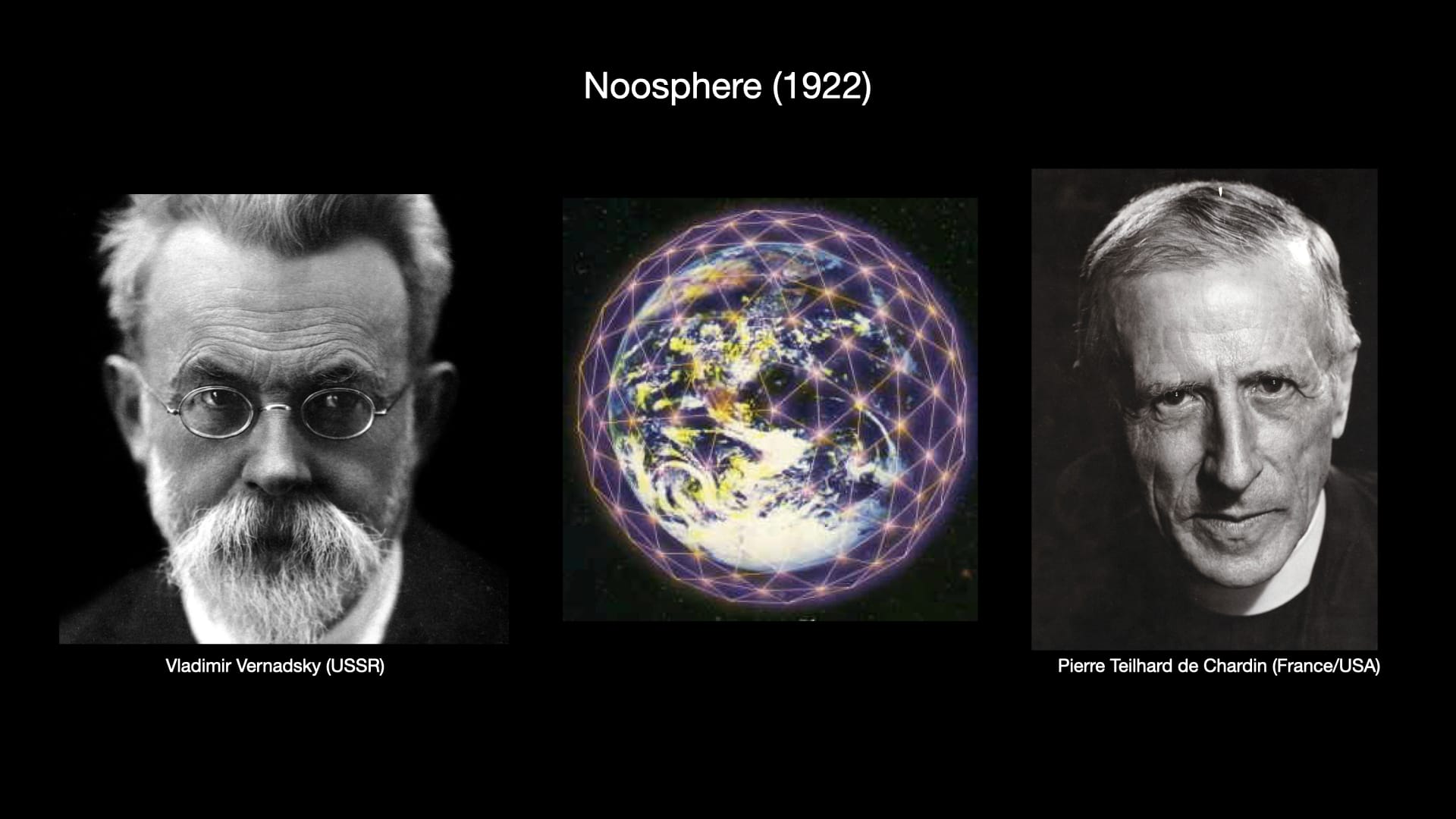

As if these forces weren't enough, other more esoteric worldviews are also influencing Western thought. The concept of the “Noösphere," developed in 1922 by French-American theologian Pierre Thielhard de Chardin, French mathematician Edouard LeRoy, and Russian scientist Vladmir Vernadsky, posits that with the rise of global communication, the world will transition into a kind of “global brain,” or “noösphere” (from the Greek no'us; knowledge or intellect).

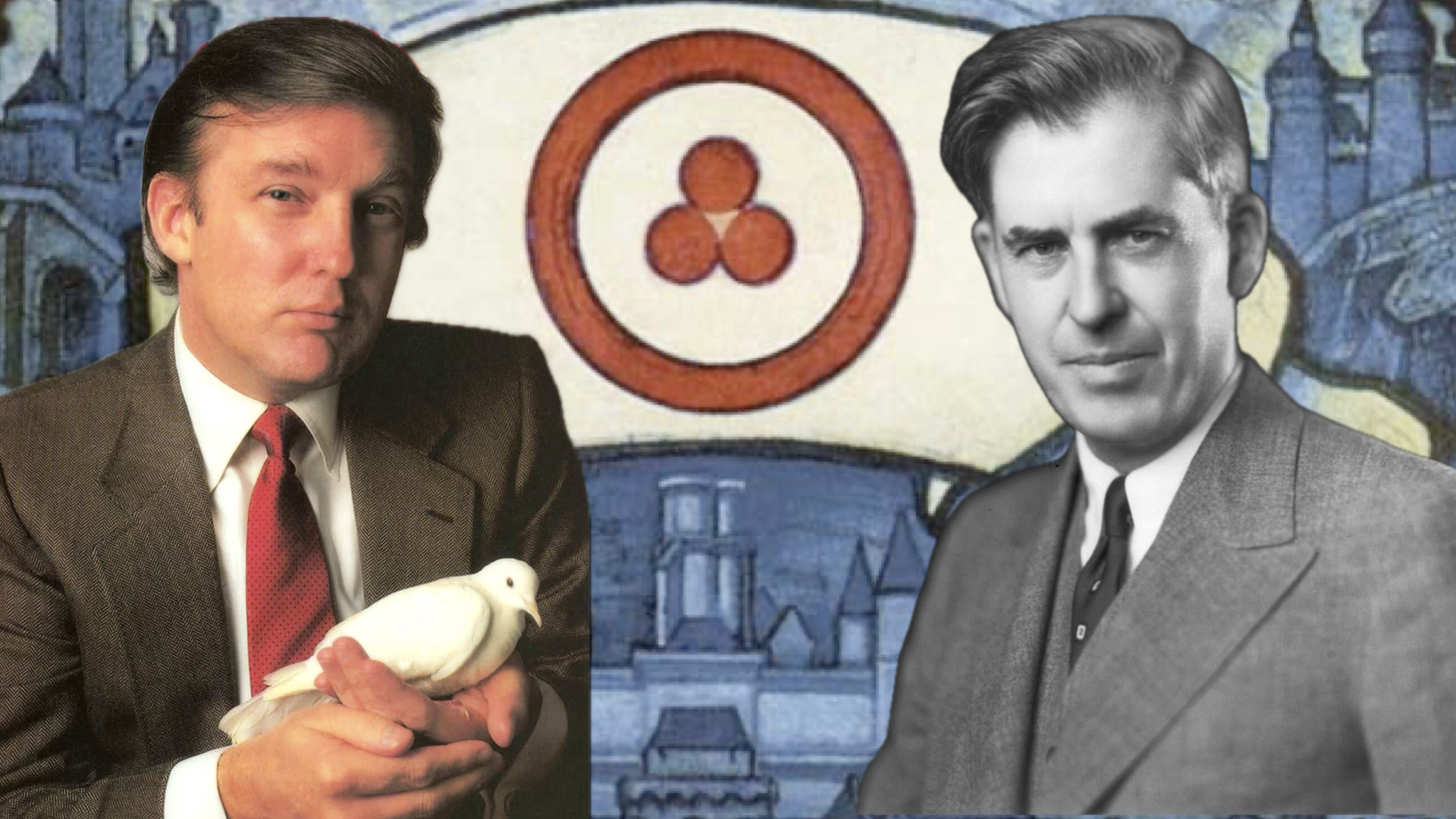

These ideas have, over time and through repeated exposure, become mainstream. Mikhail Gorbachev borrowed heavily from the Noösphere idea in developing the concepts of glasnost and perestroika that reshaped the Soviet Union. Gorbachev also drew from the ideas of Nicholas Roerich, a mystic and artist who incorporated theosophy and gnostic Christianity into his worldview; he also heavily influenced 1948 presidential candidate and former Vice President Henry Wallace.

Roerich and his followers have prophesied that the world would one day be united in a noöspheric design. There would be people who would get it (accelerators) and those who would not (inhibitors). Those who stood in the way would simply be marginalized.

Vladimir Putin has also drawn on the noösphere idea. His Chief of Staff since 2016, Anton Vaino, is best known for inventing a ‘noöscope,’ a device likely more imaginary than real, for tracking our progress as we transition into the noösphere. (Really, we're not making this up.)

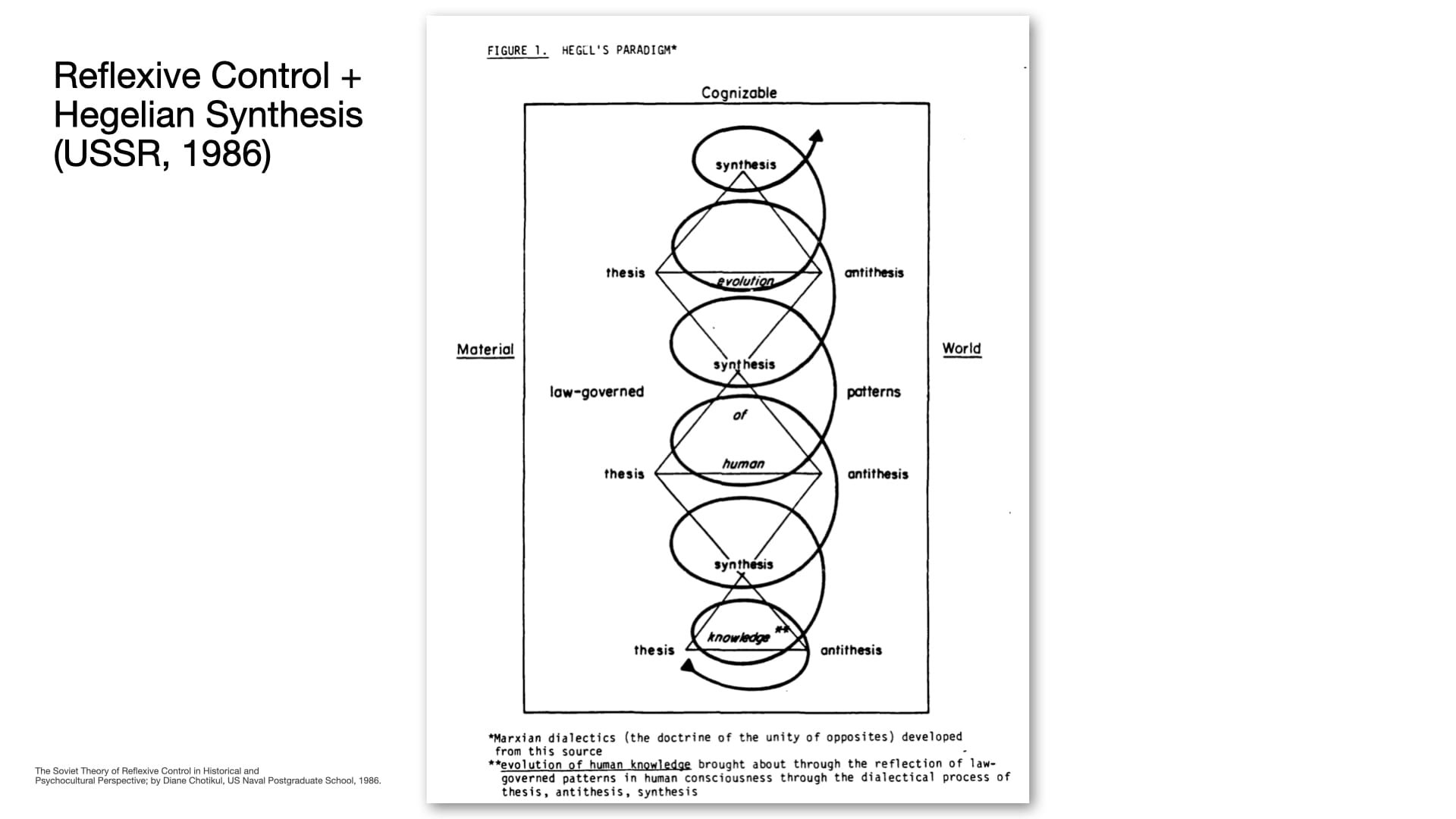

Another Russian idea, Reflexive Control, has also been used to great effect against the West. Based on a system of Hegelian dialectic thought, it pits two opposing poles against each other, thesis vs. antithesis. Through conflict, a new, desired position, synthesis is reached. In Reflexive Control, thesis and antithesis are carefully constructed to produce specific outcomes. This is manifested globally in the form of heavily caricatured versions of left and right engaging in performative conflict, and new hybrid red-brown forms emerging — bringing together illiberal qualities of both.

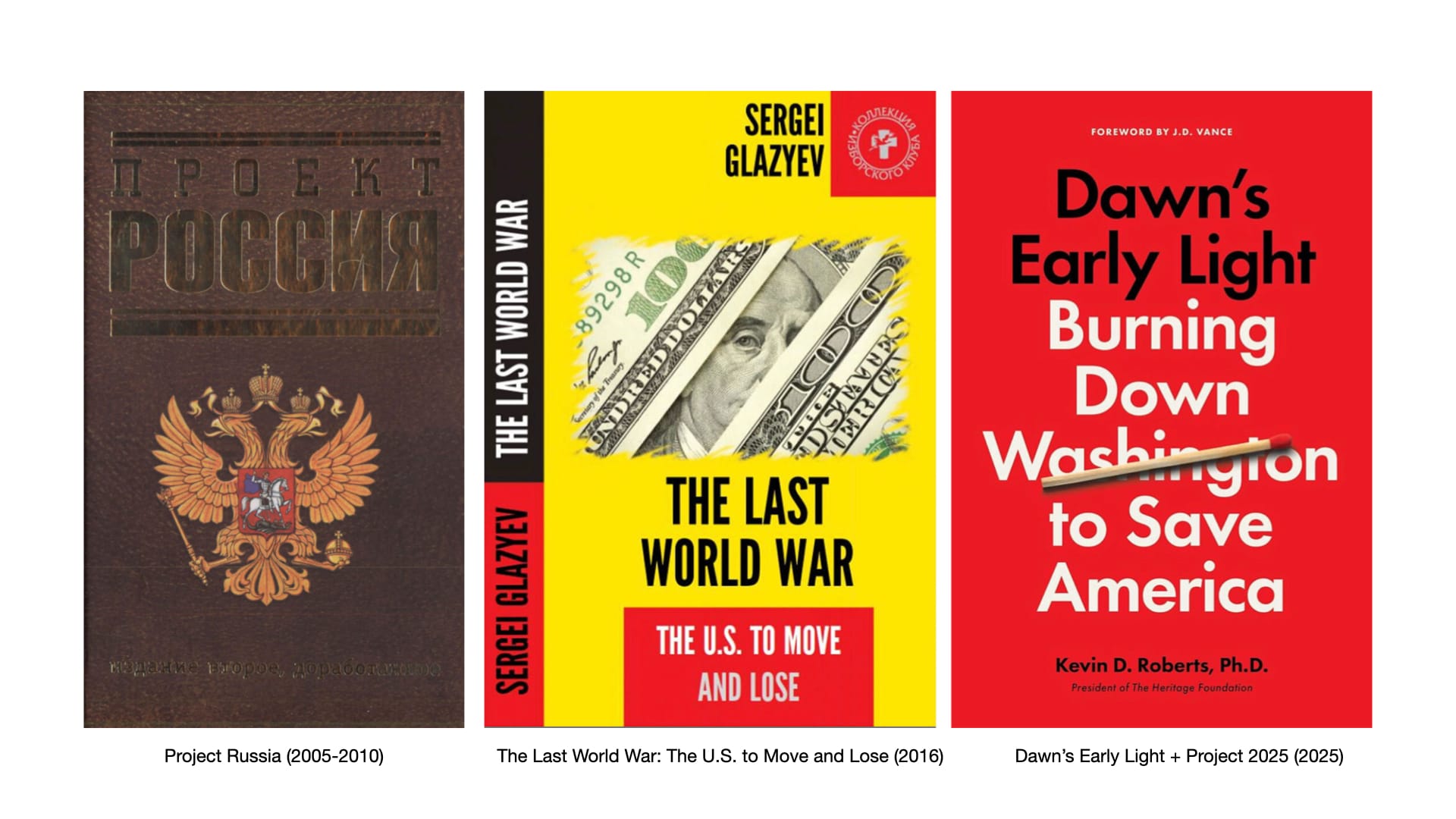

Books, podcasts, and social media have also drawn minds into the ongoing war over worldviews. Project Russia, the book series produced by the Kremlin from 2005-2010, helped shape Russian attitudes about Western democracy and argue for its elimination. Sergey Glazyev, a principal architect of the BRICS currency concept, outlines the Russian plan to end US dollar hegemony. And countless other books rooted in the ideology that advanced Project 2025 and DOGE have aimed to gather recruits.

How can we nucleate a future where democracy wins?

Many of us in the West have been engaged in defending democracy, and if we're honest, the results speak for themselves: we have failed in this task. By adopting this stance, we have been put in the unenviable position of defending the status quo — one which in very significant ways is difficult to defend. So it's time to ask a different question: how can we create a future where democracy flourishes?

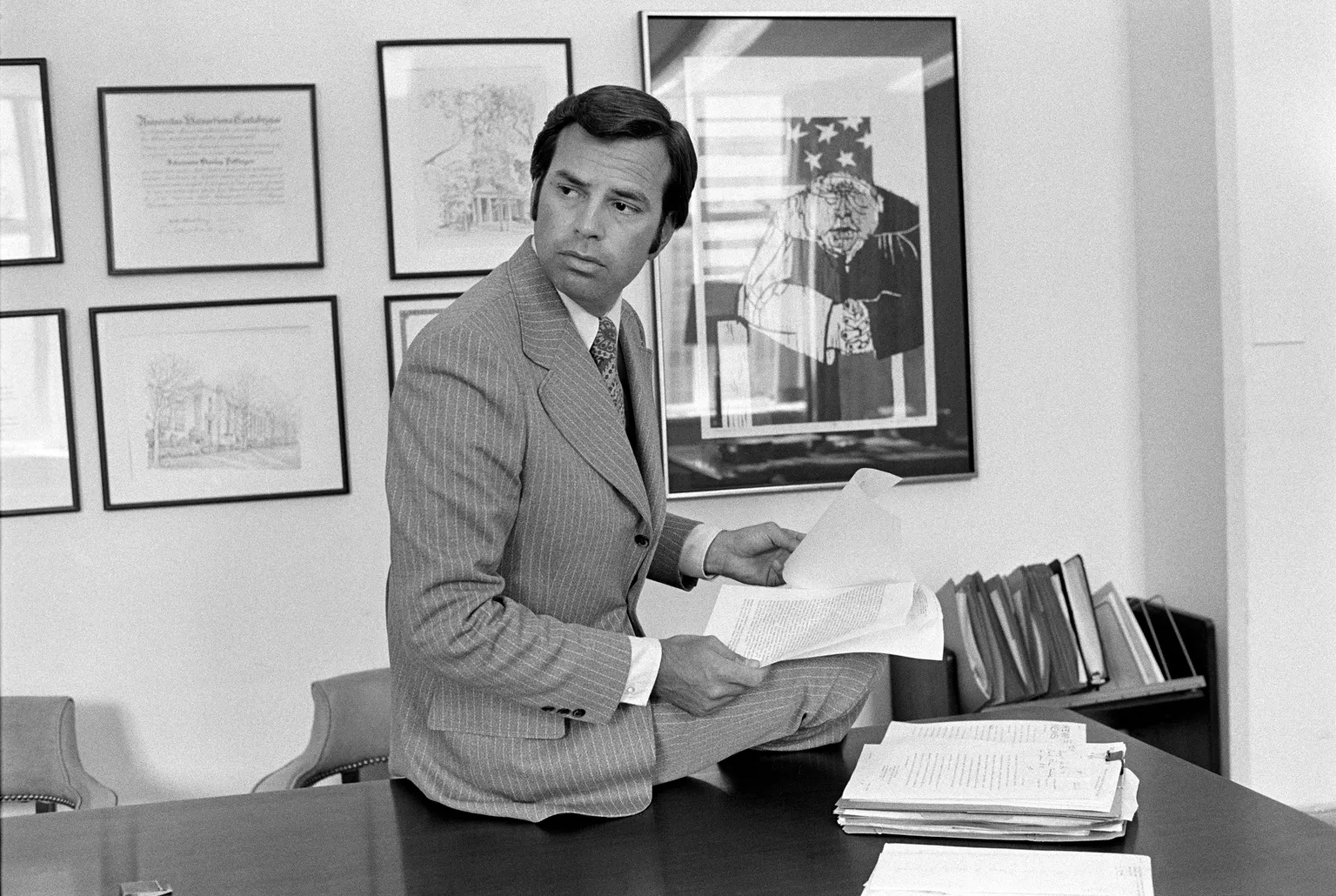

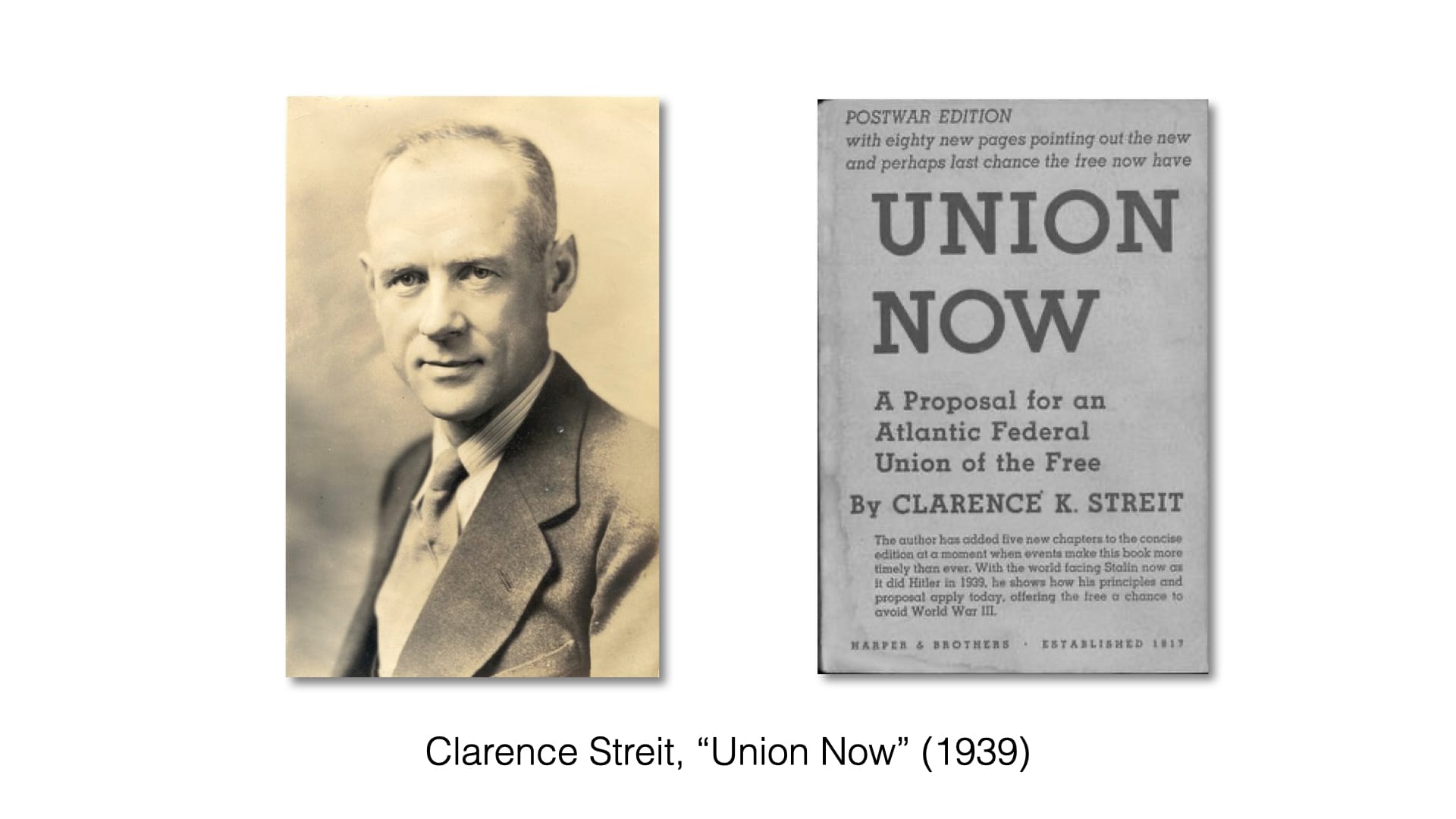

Fortunately, we are not the first people to ask this question. In 1929, Clarence Streit, a journalist with the New York Times was assigned to cover the League of Nations in Geneva. He observed its strengths and weaknesses, but was primarily concerned about whether it was fit for its purpose — to avoid another world war.

He concluded the League of Nations was doomed to failure. Despite the best of intentions, he argued that it was unworkable because of one key flaw: the unit of membership was individual countries, rather than citizens. It also lacked any incentive to favor democracy over authoritarianism.

In response, and in what turned out to be a futile attempt to ward off World War II, in 1939 Streit published his ideas in his book Union Now!, which offered this key idea: a union of the world's largest democracies where the unit of membership was the individual — drawing the basic design from that of the United States itself.

Where the 13 colonies squabbled over trade and other petty matters, the Constitution recognized their common values and fundamental shared interests. By creating a union structure with states as members, and individuals as citizens of both, those shared interests could be guaranteed at the federal level, while states could retain their own laws for local concerns. Rooted in the technology of the day (ships, horses, and mail), the scope and scale of that governance approach, spanning coastlines, made perfect sense.

Fast forward to the 20th century, with air travel, internet, television, and global trade interdependence; Streit argued that modern technology calls for a union that spans the globe.

Streit's ideas were popular — before, during, and after the war. But instead of following his design, pieces were incorporated into the institutions that shaped the Cold War era. NATO perhaps inherited the most. But rather than a political union, it is a military alliance, and its member countries have benefited greatly from its existence.

The United Nations repeated the most serious errors of the League of Nations and has been rendered ineffective through the influence of authoritarian nations. The European Union also has drawn from Streit's ideas with positive effect.

But the world he envisioned — one with a strong union of the world's democratic nations — has not yet been attempted. The benefits are clear: shared defense, like with NATO, but also common rights across member countries and less friction with trade and travel.

And it creates a clear incentive for authoritarian states: overthrow your dictators and meet the standard required to join the union of democracies. Everyone wins.

What should be done?

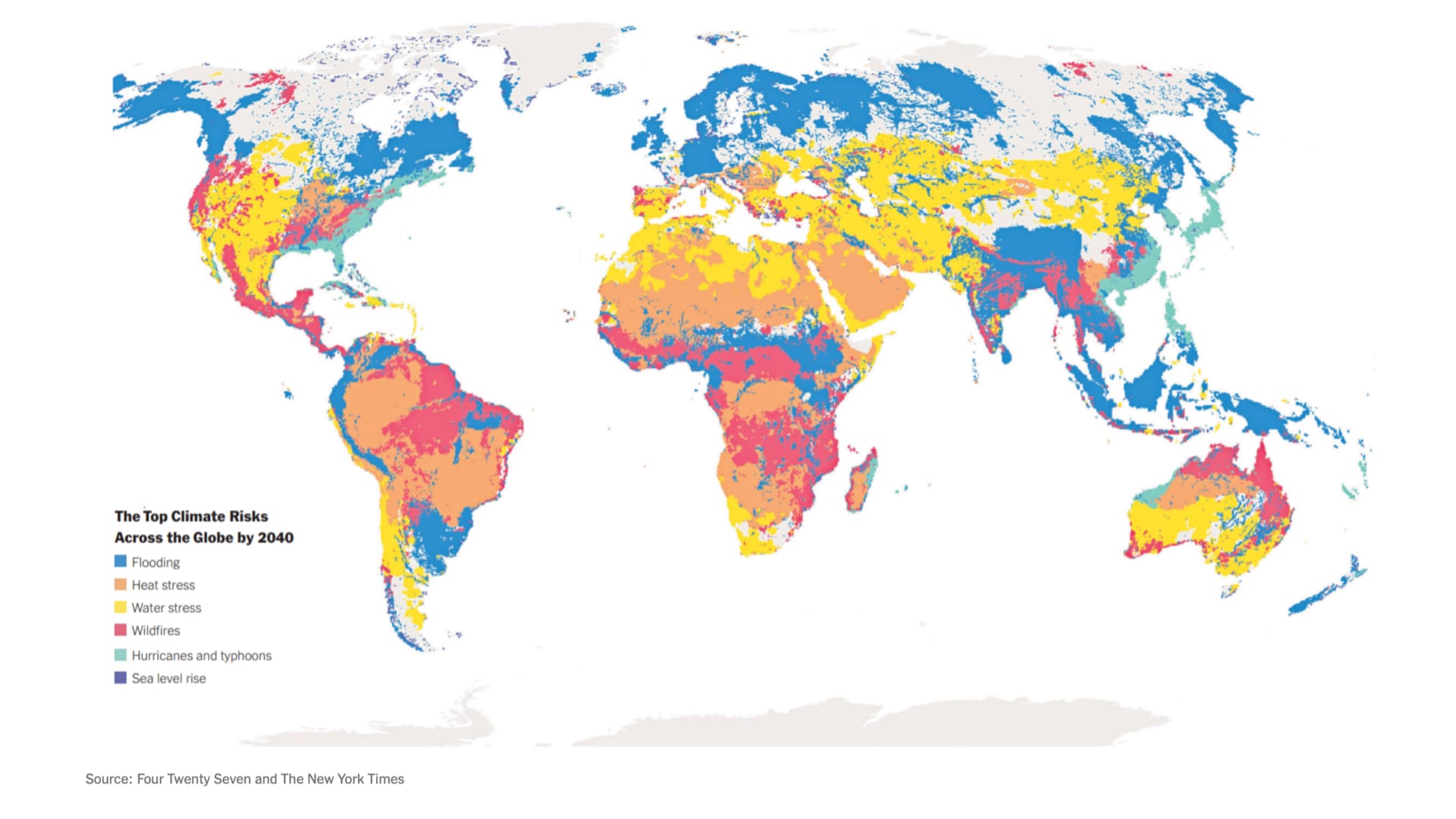

A global union of democracies might come across as idealistic or pie-in-the-sky at first. And this isn't the only idea worth considering. But consider that the noösphere is already here. Elon Musk controls Starlink, the furthest-reaching system of global communications in history, and he's not on the side of democracy. Meanwhile we're dealing with real challenges like climate that require global coordination.

The choice isn't whether to try to start building a global network of democracies, but when, and how we will begin.

Rather than merely defending democracy, fretting over each setback, it is time for us to construct a new reality that gains momentum over time. This is what we mean by nucleate, and each of us can be that nucleus within our own communities. This work will take time. And while we may not have it, the scope and scale required means this work cannot be meaningfully rushed. Deep change requires patience. It's time for us to replace shallow urgency with rightful action.

Big tech is working against us, so think differently about organizing. Instead of social media, turn towards small networks, group chats, and the open web. Host events in your area. Meet your neighbors. Build networks of contacts in other countries. Expect to spend the rest of your life on this work — and to entrust it to your kids, too.

At this point it seems very unlikely that we can turn things around through voting alone. The 20th century institutions that have carried us in the post-war era are, it seems, no longer fit for purpose.

While Streit's vision is radically different from the world as we know it today, we are called upon to pursue it (along with other related experiments) if we want to carry democratic values in to the 22nd century. If we don't, we will be left to live in a world dominated by Musk, Thiel, and Putin, rooted in the ideologies of Ilyin, Evola, Yockey, Yarvin, and Dugin. The choice is ours.

Let's start building today. ◼

America 2.0 is dedicated to the task of advancing democracy throughout the world by connecting people who share our vision. Join me, Joe Trippi, Marietje Schaake, Tiziana Stella of the Streit Council, and dozens of other journalists and leaders by joining the America 2.0 mailing list.

Additional Suggested Reading